May 21, 2024

by Daniella Alscher / May 21, 2024

by Daniella Alscher / May 21, 2024

What’s the difference between a typeface and a font?

There’s no punchline here.

There is an abundance of words that graphic designers use while they’re talking about typography, and they’re all pretty confusing–it’s an entirely foreign language to anyone outside of their world.

Before we begin, we should probably get a good understanding of what typography means.

Typography is the overall appearance of text. This means not only the font but also the height, weight, color, orientation, and size of the characters.

Confused? Keep reading.

Now that we’ve gotten that straightened out, we can get into a little more detail.

If you’re a typographer, there’s no excuse to not know the following terms. If you’re simply interested in learning more about graphic design, welcome to the typography vocabulary class. And, if you're already familiar with all this and are looking for a tool to create high-quality documents, check out desktop publishing software.

They’re just symbols. How much could there possibly be to it? Well, read on to see for yourself.

Starting with character, which is an individual symbol that takes the form of a letter, number, or punctuation mark.

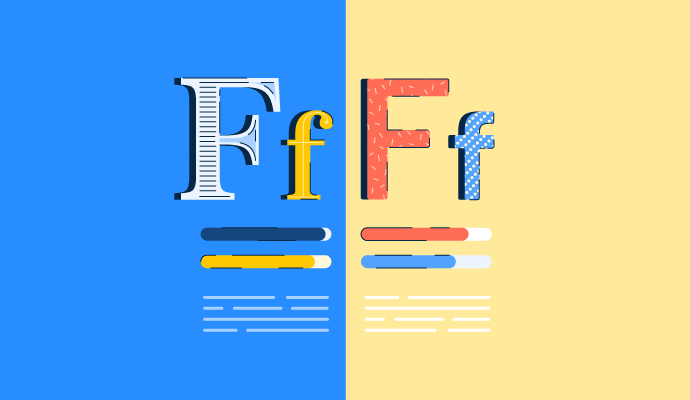

These two terms often get confused, but there is a difference between a typeface vs font. Typeface, sometimes called a font family, refers to the design of the letters and numbers (how the letters look). Font refers to the different weights and styles that are categorized within the typeface itself.

Also called an alternate character, glyphs are an abnormal representation of a character. These characters could contain an accent, be decorative, or have another variation within the same typeface.

With thousands of font types to choose from, it’s helpful to pick out the common characteristics amongst each one and categorize them.

Serif typefaces have embellishments that project from the end of each stroke of a character

Sans derives from French and translates to “without”. Sans serif characters are those without any embellishments at the end of their strokes.

These typefaces and fonts resemble hand lettering styles ranging from casual cursive to elegant calligraphy.

These typefaces, also called display typefaces, are intended for exactly that: display. Their unconventional and unrestrained looks call for their use in headers, not body text.

Where does the text fall in the design?

In general, alignment is the arrangement of something in a straight line. In typography, that “something” is the characters. Different alignment choices create different reading experiences for the viewers. Choose wisely.

The paragraph is aligned to the left, while the right side is irregular. For example, a majority of this article is aligned to the left.

The paragraph is aligned to the right, while the left side is irregular. This type of alignment is very rarely used.

The paragraph is aligned in the center, and both the left and right sides are irregularly aligned. Centered text should not be used for full documents but rather for short pieces of text such as titles, quotes, or short poems.

Justified alignment aligns both the left and right sides, making paragraphs look neat. How is this possible? There are irregular spaces placed between words in order to fill in gaps on both sides. Not necessarily pleasing to the eye.

A little elbow room never hurt anyone.

Leading is the space between two baselines in a body of text. In typography, “leading” is pronounced to rhyme with “shedding” or “bedding”. The name comes from when typewriters were used (ancient times), and lines were separated by pieces of lead. Increasing leading value gives more breathing room for the text and makes it look better, and improves overall readability.

Tracking, also referred to as letter spacing, is the spaces between characters (letters, numbers, punctuation, etc.) for an entire group of text. The amount of space between these characters is fixed. The increase in tracking space decreases the density of the typeface, and vice versa. Tracking has the ability to make the lengths of lines of text look more even.

Kerning is the spacing between only two characters (letters, numbers, punctuation, etc.). Often, the default setting for kerning in graphic design software works well, but there are some instances in which the text needs to be spaced apart further for proper readability. There is no “magic” amount of space to place between each letter - kerning is not mathematical, it’s all about perception.

There’s a lot going on behind the scenes of these characters.

An ascender is the part of a lowercase letter that extends above the x-height. For example, the letters d, f, k, and t have ascenders.

The area of the letter which is either entirely or partially closed by a stroke. The stroke that creates the counter is called a “bowl”.

The part of a lowercase letter that extends below the baseline. For example, the letters p and q are descenders.

An exaggerated extension of a part of a character, such as the serif or tail. They’re very fancy.

A decorative descender in a character. For example, the descenders on Q, K, R, g, j, p, q, and y are tails.

This is the imaginary line that marks the height of the ascenders.

This is the imaginary line that defines the height that most capital letters will reach. The cap height is used to measure the height of flat-topped capital letters.

The imaginary line marks the line where most letters within a font sit. It’s like the horizon line of typography.

Also known as a descender line, the beard line is an imaginary line that the descenders in a font will hit. If you think of descenders as beards, this is how far they grow.

Also called the corpus size, this is the distance between the baseline and the average height of the lower-case letters in the typeface. Often, this is the height of the “x” in the font, hence the name “x-height”.

Ear

EarOften found on the lowercase “g”, the ear is a decorative stroke that projects from the upper right side of the bowl.

Also known as the neck, a link is what connects (links) the bowl and loop of a double-story “g”.

In a double story “g”, the loop is the closed or partially-closed counter beneath the baseline. Loops also occur in cursive b, p, and l.

The bar, or crossbar, is a horizontal line in a letterform. It acts as a connection between two strokes.

The decorative stroke at the end of a serif character’s arm is connected by a terminal.

This is the curved stroke of the character that creates the space called the “counter”.

Another way to describe a lowercase letter.

Another way to describe an uppercase letter.

A small projection from a stroke of a character in serif typefaces.

The curved stroke projects from the stem of a character that aims downward. This occurs in h, m, and n.

The core, left-to-right stroke which curves in the letter “s”. Depending on the typeface, the spine may be nearly vertical or nearly horizontal.

A type of curve. Some consider the terminal to simply be a stroke of a serif letter that ends without a serif.

An arm or leg in typography is an upper or lower element of a character that branches off from a stroke either horizontally or diagonally. p

This is an imaginary line that bisects a character in order to determine the angle of stress in glyphs which have differing stroke thicknesses. A vertical axis indicates zero vertical stress.

A projection from the main stroke that is smaller than a serif or beak.

Like a flower, the stem is what holds everything together. It’s the primary vertical stroke in upright characters.

The change of stroke width across characters within a font. Stress can be vertical or diagonal and is measured by the “axis”. In fonts where there is no obvious change in stroke width, there is no stress. For anyone.

The lines that make up the main parts of a character are secondary to the stem. Arms, legs, bars, bowls, and stems are sometimes all referred to as strokes.

Points are the smallest unit of measurement. They are used for measuring font size, leading, and other spatial matters in both typography and graphic design as a whole. There are 72 points in one inch.

Pica is another typographic unit of measurement used in design software. It is equivalent to approximately ⅙ of an inch, or 1/72 of a foot. One pica is divided into 12 points.

Who knew typography was so intricate? There are a lot of things that go unappreciated in our world, and the fine-tuning that typographers do to our words is one of them. Typography is more than just typing out a word and printing it. It’s about tweaking and polishing every last spur and swash until the words become art themselves.

Typography is a vital skill in graphic design, but it's not the only one. Delve into the essential graphic design skills needed to excel in this creative field.

This article was originally published in 2019. It has been updated with new information.

Daniella Alscher is a Brand Designer for G2. When she's not reading or writing, she's spending time with her dog, watching a true crime documentary on Netflix, or trying to learn something completely new. (she/her/hers)

If you’ve learned a little about design, you know a designer’s most powerful weapon is their...

by Daniella Alscher

by Daniella Alscher

The design industry never stands still—are you keeping up?Visual content captures attention...

by Daniella Alscher

by Daniella Alscher

If you’ve learned a little about design, you know a designer’s most powerful weapon is their...

by Daniella Alscher

by Daniella Alscher